Adding the Easy Piece; or, The Metaphor of the Rock

The novice project manager cares about a program’s size. The experienced manager cares when it gets big.

Big programs are, from a developer’s perspective, slow. Slow not to run, but to develop: effortful to maintain, expensive to change. Half the job of a project manager is to keep programs small by keeping their requirements small (and half the job of an architect is to keep them small when the requirements are large); this is about the case when this isn’t enough.

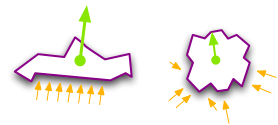

Developing a program is like pushing a rock around a room. (The rock is called “code base”. The room is an irregular shape called “design space”, with “requirements” marked off along the wall.) Big programs are big, heavy rocks. They require more push, to get less far.

Sometimes you can get several people to push one rock. This works if the rock is the right shape - if it’s straight and wide, say, so that many people can push it the same direction, at the same time. Otherwise they will push at different angles, and the greater part of their efforts will cancel.

Sometimes, you can break the rock

into smaller pieces - so that different people can push them, or so that you can

push them separately, or so that you can abandon some pieces and use instead

pieces that are sited where you’re going. (The advantage of a pre-sited piece’s

location can outweigh the fact that it’s not quite the right shape.)

Sometimes, you can break the rock

into smaller pieces - so that different people can push them, or so that you can

push them separately, or so that you can abandon some pieces and use instead

pieces that are sited where you’re going. (The advantage of a pre-sited piece’s

location can outweigh the fact that it’s not quite the right shape.)

Sometimes you can polish the floor, or insert rollers, or employ a cart (use languages, platforms, practices, tools). Sometimes, though, you spend more time polishing the floor than you would have spent moving the rock; and sometimes the rollers end up aimed differently from where it turns out you need the rock. But even when these tricks work, they only increase the size of rock that’s counts as “big”. Some rocks are still big rocks.

This perspective - the size of the rock - is the static view of code size. It’s concerned with how to move rocks of a fixed size. The static> view is the right view for maintenance programming. It’s the right view for (most of) version three of a product, where most of the program is unchanged from version two. Often it’s the right view for version two as well.

For a greenfield project - a project where you’re (mostly) not modifying an existing system, but (mostly) starting from scratch - the static view is too limited. In a greenfield project, you’re not just moving the rock. You’re building it too.

(How do you build a rock? By fastening other rocks to it. Or sometimes by coating chicken wire with papier-mâché, if you just need to know how it looks.)

Greenfield development sounds simpler. Instead of pushing the rock where it’s needed, you just build it there. There’s some work (pushing) that you don’t have to do.

But oh, did I mention that you won’t know where the rock needs to go until you’ve already built some of it? (Funny how often that isn’t mentioned.) In fact, you may have even less of an idea where to site the rock that hasn’t been built than one that has, because the shape of the rock helps determine the site, And if a rock takes long enough to build, the room may change too.

So, you’ve got to build the rock, and you’ve got to push it, and you could do these in any order (build some, push some, build some more, push some more), except that you won’t know where to push it until you’ve got some built. And just to make this harder - and more realistic - there’s some parts you can’t build where you start, but only where you push it to.

This is the dynamic view of code size: that code size changes over the course of a project. The fundamental question about dynamic code size is: Does it matter what order you build the rock? If you know you’ve got to add a piece, does it matter whether you add it at the beginning or end of the project?

And the answer is yes, it matters. Sometimes greatly. Sometimes enough to determine whether you can build, and push, your rock at all. The reason is because building the rock makes it harder to push.

Often, on a project, there’s a few pieces that you know at the outset need to be there. They’re standard parts, that need to be attached to every project. You know how to attach them. It will be comforting to do so.

(Sometimes these pieces have names like “localization”, “optimization”, and “scalability”; or “graphic design complete”; or “windows compatibility”; or “undo”.)

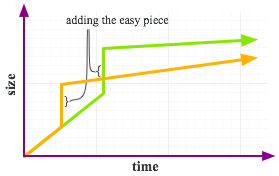

Some advantages of attaching these pieces early are: an easy sense of accomplishment, and a feature checked off. They simulate great and early progress. The disadvantage is that they increase project drag. Attaching them makes pushing the rock harder. Make it harder sooner, and you’ve made your trajectory like the orange line, and not the green one, below.

It’s not that you should never add these pieces first. Building and pushing rocks is engineering; and engineering is the art of the trade-off.

Here are some reasons to add a piece sooner. You don’t know if you’ll be able to add it later, or if you’ll have time if you wait, or how long it will take. (You want to front-load uncertainty and risk.) Or: you need to show the rock to somebody, and they can’t imagine what it will look like with the missing piece. Or: you can’t imagine this either. Or: knowing how to add a piece gnaws at you — it’s a distraction — and you can’t concentrate on harder work until you’ve added the easy piece. Or: the rock is useful only halfway built, and the piece is the useful one. Or: you’ll have to tear the rock apart to attach a piece later, and this is more work than pushing a bigger rock now.

Engineering is the art of the informed trade-off. These reasons to make a rock bigger sooner are (can be) good reasons. Weigh them against the cost of pushing a bigger rock.