Division-free LCM

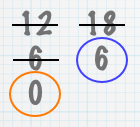

Division-free GCD

A few years ago I described an algorithm for computing the greatest common denominator without division. (Euclid’s algorithm requires division, in order to compute the remainder.) Although less efficient than the standard algorithm, I found it easier to teach to my children when they were learning to add fractions.

I’ve made a movie of the steps involved here. (The Quicktime player has a bug: if the movie plays the first step over and over, try waiting it out, but if it doesn’t get past the first step after three or four times, then press your browser’s Reload button.)

Division-free LCM

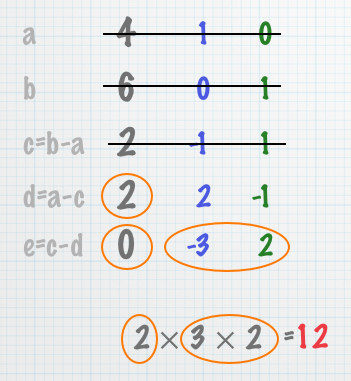

Yesterday Paula Feynman asked me if there was a similar algorithm for finding the least common multiple. I came up with this one on the drive home. It can be used at grade school level — my children learned it in about half an hour — and I used their help (and the influence of Edwin Hutchins) to figure out a teachable presentation.

The movie is here. (As before, if the movie plays the first step over and over, try waiting it out, but if it doesn’t get past the first step after three or four times, then press your browser’s Reload button.)

Euclid, Meet Gauss

This algorithm is a great warm-up for Gaussian elimination. The numbers in the second and third columns are co-factors: their respective products with the two inputs sum to the number in the first column. (This is why the first two rows are initialized to the identity.) From there down, it’s Gaussian elimination: replace a row by a linear combination of rows, until the leading term in one of them has been annihilated. Since there are only two rows, you can work in place (by extending the table downwards), instead of copying the matrices to a new location each time.

The difference between this algorithm and standard Gaussian elimination is in the set of permissible operations. Since this algorithm doesn’t allow you to divide a row by a scalar (alternatively, to multiply by a non-integral rational) in order to produce unity, you’re limited to operations within the ring of integers. This restriction ensures that the operations preserve the number-theoretic properties of the inputs, which is what lets you recover the GCD and its co-factors at the end.

Sure enough, after I showed my son how the algorithm worked, I was able to easily show him how to invert a matrix in order to solve a family of systems of equations. (He had already worked with systems of equations in school, and we had worked on representing a system as a matrix last week.)

Nothing New Under the Sun

While writing this posting, I discovered that the division-free technique for computing the GCD was actually Euclid’s original algorithm.

Similarly, I belatedly found that most of the technique for computing the LCM of two numbers was also previously known (probably as of a century ago?). The “table method” of the “extended Euclidean algorithm” computes the co-factors, in pretty much the same way. However, that method, at least as described at Wikipedia, stops short of actually computing the LCM. It also relies on modular arithmetic; I think my version is more useful for elementary education. So maybe I’m bringing something to the table — so to speak.