Constraint Diagrams

Decisions involve tradeoffs. Time at work subtracts from time with your family; money saved for the future subtracts from goods and services now; many food choices trade off among taste, convenience, price, and nutrition.

Some tradeoffs in computer science are the cost to update versus the cost to search, and execution time versus memory consumption. Tradeoffs in software development include implementation time versus execution time, and compilation time versus object code quality. Tradeoff in project management include resource pool size versus communications overhead, and cost versus time versus quality. These tradeoffs are some of the tradeoffs, respectively, in such tasks as choosing a data structure, algorithm, or cache size; choosing a programming language, a compiler and compiler settings; and choosing a project team size and personnel.

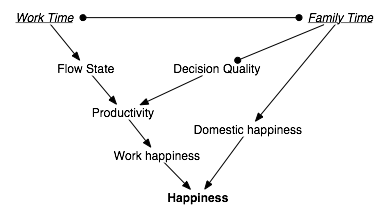

Often the factors involved in a decision are more complicated that A versus B. More time at work makes me happier, and more time with my family makes me happier too, but the contributions are different and non-linear. To some extent, I can sidestep the tradeoff between work time and family time by sharing my work with my family and vice versa, but this has different effects on different aspects of work: I make better decisions when I talk over the less technical aspects of what I do, but I can only achieve the flow state necessary for sustained technical work when I’m working alone. Family collaboration facilitates decision making and inhibits flow state; effective decision making and flow state both facilitate work enjoyment, which facilitates happiness.

This is a degree of complexity that it’s hard to keep in your head, and keeping it in your head makes it hard reflect on it. (The more of your system bus you’re using to refresh volatile memory, the less is available for computation.) Hence the constraint diagram.

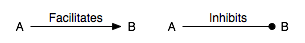

A constraint diagram represents the factors in a decision. Lines between nodes represent interactions between factors. Arrowheads represent facilitation (increasing A increases B), and circles represent inhibition (increasing A increases B).

(The terms and symbols are from neural mapping. Substitute “promotion” for “facilitation”, and this is also the language of gene expression.)

A tradeoff is a choice between two mutually inhibitory factors. If increasing A decreases B, and vice versa, then a decision about the settings of A and B involves trading off between them.

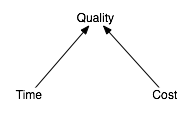

Let’s look at a classical project management tradeoff: the three-way tradeoff among cost, time, and quality. There are a couple of ways to look at this tradeoff. One is by listing “cost” and “time” as factors which facilitate to quality:

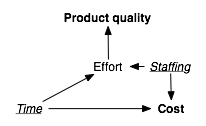

The advantage of getting this onto paper is that it makes it easier to unpack the factors. Time vs. cost vs. quality is a simplistic way of looking at this. The diagram below illustrates the way that time, cost, and quality interact. The project manager controls time directly, but not cost: cost is an emergent property of staffing. Borrowing from the language of statistics, time and staffing are independent factors (they’re under the decision maker’s control), and everything else is a dependent factor. Cost and quality are the goal factors: they’re what the decision maker is trying to optimize. I’ve indicated independent factors and goal factors typographically in this diagram and the ones that follow.

(This model, which is still very simplified, is of a non-capital-intensive project that’s managed to a date, such as a software project with a hard launch date. Building an airplane or writing incrementally deployed software would have different independent factors.)

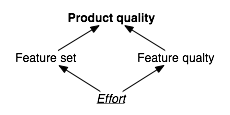

To make the model more precise, we can zoom in on, and expand, the relation between effort and quality. Effort can be spent either on the feature set, or on the quality (usability, extensibility, low defect rate) of the substrates and of individual features. Both of these factors contribute to the overall product quality:

Returning to the example at the beginning of this posting, of the family-time vs. work-time tradeoff, the following diagram represents graphically the factors that I described in text above. Like the time-cost-quality diagram above, it’s still simplistic (my family is happier when they participate in my decisions, and this makes me happier too, and also increases the amount of time they’re willing to let me spend away from home, which increases the time I have to get into a flow state), but it’s already an order of magnitude more than the degree of complexity that I can comfortably hold in my head.

Over the next few weeks, I’d like to explore the use of constraint diagrams to represent some tradeoffs in software engineering, especially where these tradeoffs intersect my other interests: software development, productivity, and the use of abstractions and high-level languages.