Web MVC

The Model-View-Controller (MVC) architecture is a standard architecture for interactive applications. In client-server programming, the MVC components are distributed across at least two nodes of a network. This leads to a set of choices about where to deploy each component of the architecture. One solution is the traditional server-based MVC model. Another is the Rich Internet Application (RIA) model. In a real-world application with client-side validation, these are more similar than they might seem.

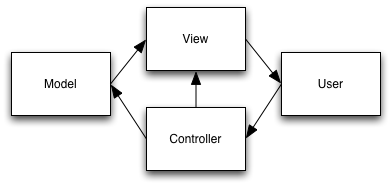

Desktop MVC

In an interactive application, there is typically a domain model, code to present the model to the user, and code to act upon the model in response to the user manipulation of input devices such as the keyboard and mouse. For example, in a word processor the domain model is the document, which contains entities such as paragraphs, spans, and styles. The system presents the document to the user as (for a sighted user) glyphs rendered as pixel patterns, and interprets keystrokes and mouse actions as edit, formatting, and control commands.

Smalltalk-80 introduced the Model-View-Controller (MVC) architecture for structuring this type of application. MVC separates the maintenance of the domain model (the Model), the presentation of the model (the View), and the interpretation of user input (the Controller).

Model-View-Controller Control Flow1

Together with the User, the components of an MVC architecture form two cycles of data and control flow:

-

The View Cycle: User -> Controller -> View -> User. The user manipulates an input device — for example, by clicking the mouse button, while the mouse cursor is positioned in the down region of a scroll bar. The Controller responds by sending a message to the View (e.g., by invoking

view1.scrollDown()). The View updates its state (it adjusts the value ofview1.xoffset), and updates the information that it presents to the user (callsbitbltonview1’s screen area, and invokes thedraw()methods of views that intersect the accumulated damage region). -

The Model Cycle: User -> Controller -> Model -> View -> User. The user manipulates an input device in a different way or in a different context — for example, by pressing control-D while an entry from a list of contacts is selected. The Controller updates the state of the Model, the view updates to match the model, and the user is presented with the updated view. For example, when the user selects the

Deleteitem from a menu, code in the Controller might invokeview.deleteRow(), which invokesview.currentSelection.delete(), whereview.currentSelectionis a Model object andview.currentSelection.delete()is a Model method. Thedelete()method changes the Model data, which notifies these objects’ Listeners, say by invoking theirregisterChange()methods. The set of Listeners includes View objects, which respond to the invocation by updating the display.

In a desktop application, the Model, View, and Controller run on the machine that the user interacts with. This kind of application is easy to write (or, as easy as the domain model allows); it easily takes advantage of client platform features such as dialog boxes, offline storage, and drag and drop; and it’s responsive. The disadvantages of desktop MVC architecture are the disadvantages of desktop applications in general: they are difficult to deploy, they tend to be platform-dependent, and they are generally limited to manipulating data on the local file system2.

Web Application Programming

In a web application, the server software runs on a server, and the user interacts with browser software running on a client. The Model’s data is stored on the server. The user interacts with software running on the client.

Client-server programming is difficult because the program is distributed across more than one network node. Some code has to run on the client to interact with the user. Other code has to run on the server to interact with the data store.

In the case of a web application, the code that runs on the client includes the user agent, or browser. The distributed nature of a web application creates two challenges. One is that the application has to render data from the server into a context where it can be displayed on the client. The other is that information about user events has to get back from the client to the server.

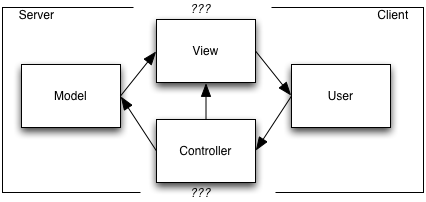

The architectural decision about client-server MVC is which components to deploy to which nodes, and how to manage the communication between them. Should the View and the Controller run on the server, or the client? What about the Model?

There’s a variety of ways to make these decisions. One solution is Server-Side MVC (below). Another is the Rich Internet Application architecture (also below). But all the solutions have some elements in comment, because of the following ground rules:

- At least part of the Model has to run on the server. This is because the Model is responsible for maintaining the integrity of the business objects, and has to be immune from client spoofing. It also synchronizes changes requested by simultaneously executing clients if the changes are bottlenecked through code that runs on the server, although in a clustered server environment this doesn’t come for free.

- The user has to be able to see the information presented by the View. This means the View, no matter where it runs, ultimately must control the display of this information on the client.

- The Controller must be able to receive events that represent user activity.

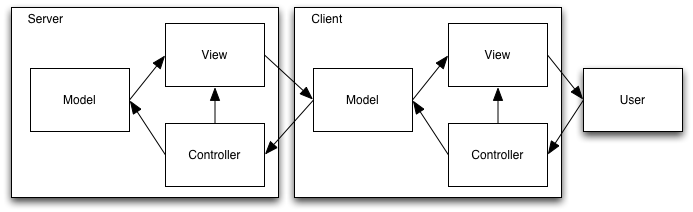

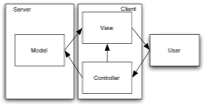

Server-Side MVC

In Server-Side MVC, the Model, View, and Controller run on the server. The View generates a representation of a presentation. This representation is downloaded to the client, which displays it. User interactions with the client are sent back to the server, where they generally result in the generation of a new presentation, which is downloaded in turn, and updates the previous presentation. This is the view update operation.

Server-Side MVC

In a Server-Side MVC web application, the View generates an HTML page, which is sent to the client as an HTTP response. The browser, on the client, encodes user events as the URL, query, and POST parameters in an HTTP request. The Controller, on the server, interprets this information as Model or View changes, and routes the request to the View, which responds with another HTML page. The view update operation in a web application is implemented as wholescale replacement of the previous view by the new view. In a browser, this is the page refresh.

In the Java community, “MVC” means “Server-Side MVC”. In this context, (Server-Side) MVC is also called Model 2. (Model 1 was a server-side application without the architecture.) JSP, Struts, and PHP are all specific technologies that can be used to implement Server-Side MVC.

The advantage of Server-Side MVC for the developer is that if the Model (aka business logic) is running on the server anyway, this architecture allows the developer to use the same language, libraries, and data structures to write the rest of the application, and local procedure calls to communicate between components.

The disadvantage is that the quality of the user experience is limited by three factors:

- View updates in Server-Side MVC are more coarse-grained than they are in a desktop application. A Server-Side MVC application can’t generally update just part of a view (or an interior node in a view hierarchy); it has to create an entirely new view and replace the old view by the new one, even when the new view is almost identical to the old one[10]. The user experience correlate of this limitation is the ubiquitous full-page refresh in Server-Side MVC applications.

- User events in Server-Side MVC are more coarse-grained than they are in a desktop application. Multiple client-side user events, such as a series of clicks and keystrokes, are aggregated into a single HTTP request that summarizes their effect. This has implications for the kind of feedback that the Controller is able to give; it’s why direct manipulation such as drag and drop is impossible in this architecture, and why client validation is difficult.

- The previous two problems are the special cases of the problem that the bandwidth of communication between the user and the application is low. The latency of communication is also high, compared to desktop interactivity — any Model cycle, or View cycle that involves a page refresh, is an expensive and offputting activity.

Server-Side MVC is the path of least resistance towards developing an application that provides access to an existing Model implementation. It allows the incremental expenditure of developer resources towards a limited degree of user interactivity. For many applications, only limited interactivity is required. This is especially true for non-consumer web applications: both the users and the organization would rather have developer resources go towards back-end improvements and new business features, if these resources are coming out of the same pool that improvements to the user experience would come from.

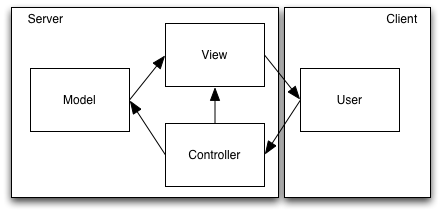

Server-Side MVC: Under the Hood

Let’s look again at how the user interacts with a Server-Side MVC application. The View in a Server-Side MVC application isn’t actually displaying information on the user’s screen or to the user’s screen reader; it’s creating data which will instruct the user’s browser to display this information. The Client isn’t reading the state of the input devices; the browser is reading this state and summarizing it into HTTP requests.

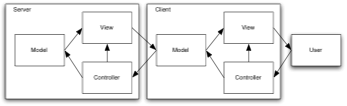

The diagram above hid this complexity by conflating the User and the User Agent, and placing them both inside the computer. (That’s why the User was inside the computer in the Server-Side MVC diagram.) But the human user doesn’t interact directly with the HTTP and HTML protocols. There’s actually an additional piece of software — the browser — mediating the interaction of the user with the server component of the application. The browser has its own Model, View, and Controller. The browser’s Model is the HTML page. The View renders the page to the screen or screen reader, and the Controller interprets the keyboard and mouse events against the input focus state and the position of rendered elements (such as links and form elements) within the browser window.

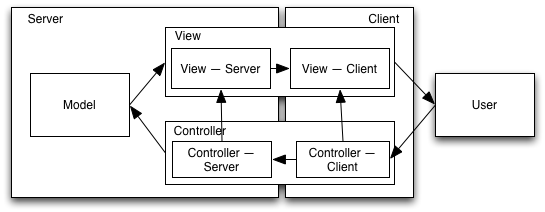

Server-Side MVC unpacked (slightly)

This is still (a variant of) an MVC architecture, it’s just that the View and Controller are each split between the client and the server. The high-overhead HTTP request/response transactions occur within components: the back-end View communicates via HTML to the front-end View, and the front-end Controller communicates via HTTP to the back-end Controller.

Cycle Time

There’s an additional complication, which is that now there are two View cycles. User actions that don’t involve a page refresh, such as scrolling the page or choosing a new form element, initiate a Client View Cycle. Actions that require a page refresh, such as paging to the next ten items in a list, or searching for products that contain the term “AAC”, initiate a Server View Cycle. Neither of these actions changes the Model — they’re both View cycles, not Model cycles — but they require different kinds of changes to the View.

Cycles that cross the client-server boundary — the Model Cycle, and the Server View Cycle — are more expensive than cycles that are encompassed within a single node.

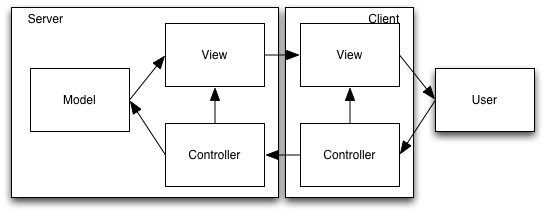

The Client Thickens

The final step in fleshing out the diagram above is to account for input validation, such as checking that a credit card number has the right syntax or that input field co-occurrence restrictions hold (if menu item 1 is selected, then input field 2 must be non-empty). Given the expense of a View Cycle that involves the server, it’s desirable to do as much input validation on the client as possible, to avoid the page refresh. Since the input is validated against the model schema, this requires downloading a little bit of business logic to the client.

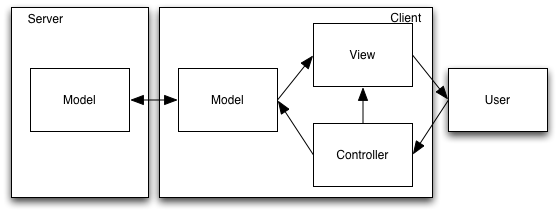

Server-Side MVC unpacked

We could draw this as a special case of single-Model MVC, just like we did when only the View and the Controller were split between the server and the client. The Model in this interpretation contains multiple components: a server-side component which runs on the server, and at least one client-side library which the View links into the HTML page that it downloads to the client.

This isn’t a thick client, or a Rich Internet Application. The only code running on the client is the browser, and whatever the current page includes. This is still the world of Server-Side MVC, as produced by JSP, Struts, CGI, or other server-side technologies that generate HTML+JavaScript. All that’s changed is that the architecture diagram now reflects (more of) the software’s full complexity.

That complexity includes the real world application of what are still research topics in academia: staged programming for multiple-target code generation (Mac IE, Windows IE, Netscape, Mozilla, Safari, Opera), process migration, and (usually manual) CPS conversion to maintain program state across pages. No wonder web programming is hard!

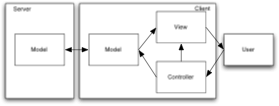

RIA Architecture

For comparison, here’s an RIA architecture. In this case, the RIA includes a domain model, in order to support client interaction.

Conclusion

When I started working on RIAs, I thought I’d find the comparison between RIAs and conventional server-side applications would look like this:

| Server-Side MVC | RIA |

|———————————————|—————————————|

|  |

|  |

|

These diagrams makes RIA architecture look more complex than server-side applications. But it turns out that server-side programming is plenty complex, it’s just that the complexity isn’t represented in the left hand diagram. That diagram conflates the User and the User Agent. It doesn’t take into account interactions between the User and the User Agent, but takes them as a monolithic whole. This makes the surface architecture simpler, because the architecture isn’t at enough level of detail to represent the kinds of interactions that determine the user experience, which include the user’s interactions with the browser.

These diagrams also simplify the architecture of (many) RIAs, which need at least some of the model in order to support RIA functionality.

Once the architectures are fleshed out, the comparison looks more like this:

| Server-Side MVC | RIA |

|---|---|

|

|

This makes the RIA architecture look simpler than Server-Side MVC, because it’s only got one view.

Let’s return from architecture astronaut space to earth. The RIA architecture may look simpler on paper, but it can still be a more complicated deployment story. It’s only simpler overall if there’s a significant amount of client-side programming anyway.

Notes

Google for MVC !/images/mvc/mvc-sampler.png (MVC Sampler)!

-

This may not be your father’s MVC. Sometimes the User is omitted from the diagram. (The user is integral to the control flow, but isn’t part of the software architecture, after all.) Sometimes the arrow from Controller to View is missing. (Presumably you can’t page or scroll in these applications, or else the state of the presentation is considered part of the Model.) Sometimes there are extra control flow or dependency arrows; and sometimes there are extra components, representing the Store that backs the Model, or who knows what else. But none of this variation makes a difference to what I want to talk about in this post, which is what happens when there’s at least a Model, and Controller, a View, and a client and a server. ↩

-

Just because the Model runs on the user’s desktop machine, doesn’t mean that the Model’s Store is the local file system. That’s just the path of least resistance, and the typical use case for a desktop application. Putting the store somewhere else is an uphill battle for a desktop application, but comes for free with a web application. Conversely, supporting interactivity (e.g. responsive feedback, direct manipulation) is an uphill battle for a server-application, and comes easily with a desktop application. ↩