Rethinking MVC

In the Model-View-Controller architecture, the Model is decoupled from information about the user interface. In a Data-Driven Presentation, the data contains all the information necessary to assemble the user-interface elements. These design patterns appear at first to be exclusive mutually exclusive: either the data contains presentation information, or it doesn’t. This apparent conflict is because of a confusion between the Model of MVC, and the Data in DDP.

Two Architectures

MVC

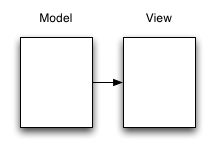

The Model-View-Controller (MVC) architecture consists of a Model, which simulates a real-world or “business” object, and a View, which represents the user interface of the object. (There’s also a Controller, but I’m not going to talk about that here.)

The Model contains objects that represent the state and logic of a business object such employee or a book. The View contains object-specific views that encapsulate the state and logic necessary to present a Model object to the user.

DDP

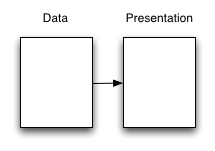

MVC is great architectural pattern. Here’s another pattern. In a Data-Driven Presentation (DDP) architecture, an application’s presentation is specified declaratively, by data structures that are interpreted as declarations about the presentation elements. This is sometimes called “data binding”. LZX is an example of a language that does this.

Two’s a Crowd?

The apparent problem with DDP is that it’s not clear what the model is. DDP doesn’t play well with MVC.

If the data models business objects, it shouldn’t be cluttered with presentation specifics such as whether a row of a data grid should be colored white or blue. But if the data contains all the information necessary to drive the presentation, it should contain this presentation-specific information.

Rethinking Data

The problem comes from thinking that “data” is the same as a “model”, and that the distinction between the MVC Model and View is the same as the distinction between data and code.

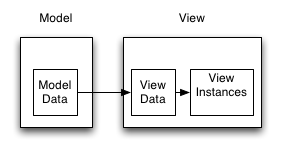

Data is a declarative description of anything, whether it’s business objects such as employees, or presentation objects such as views. The Model in MVC is a description of business objects, whether it’s a declarative description such as a database or a procedural description such as the methods in a class that implements these objects. And the View in MVC is a description of the presentation, whether it’s declarative data, procedural code, or some mixture of the two.

This leaves an MVC implementation free to contain data that describes the business objects, in the Model, and data that describes the presentation, in the View. In other words, MVC and DDP can be combined.

An Example: the Laszlo Blogging Widget

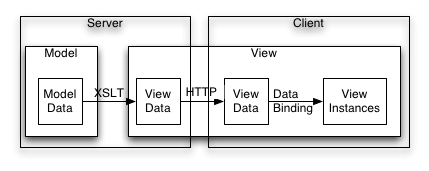

The need for this kind of architecture came up in a blogging widget I prototyped recently. The widget is a combination blogroll and aggregator intended for use in a web page gutter. It reads an XML configuration file, which names a list of RSS feeds. The back end aggregates the RSS feeds named by this file, and normalizes them into RSS 1.0. One reason to normalize them is because the structure of the resulting file is used to directly drive the presentation. But does this mean that I’ve created a data structure (the aggregated normalized XML document) that breaks the abstraction boundaries of the MVC model, by encoding properties of the View?

No, because this data structure isn’t in the Model, it’s in the View. The Model data sets are the channel list and the RSS feeds; the structure that the stylesheet creates from this reflects the structure of the presentation, and is part of the View.

An alternative would have been to write procedural code that interprets the Model data and creates individual view instances from this. In this case it would be clear that the procedural code was part of the view. Replacing this procedural code by declarative code shouldn’t be viewed as taking a step backwards in architectural clarity. Instead, it simply illustrates that declarative code (data) can be part of the MVC View.