Newer Math

Seymour Papert used to tell a story contrasting the practices of medicine and education, in order to illustrate how little the latter has improved. Place a physician from the previous century in a modern operating room and he1 won’t have a clue about what to do. Transport a teacher forward in time and they’ll fit right in. The moral is that the practice of medicine has made great strides during the last century; the practice of education hasn’t progressed at all.

I used to believe this story, and maybe it was true in the sixties. But in 1998, when I was looking for school for my rising kindergartner, I sat in on a number of elementary school curriculum nights. Among them was a presentation by the math teacher Bob Lawler2 at Shady Hill School. This was the first time I’d set foot in an elementary school in 25 years, and things had changed. Math today, at least in the better schools, is taught nothing the way it was when I was a child.

Since then, I’ve had four years of indirect experience with the math curriculum at the Milton Academy Lower School). At these schools, math facts (addition, multiplication tables) are taught in second and third grade, but prior to that and continuing through it there are open-ended group projects, grounded both in other subject areas and in fun problems – the types of problems that mathematicians I know like to attack.

Grade Two for Gauss

One question from my son’s second grade was how many candles are needed for all the nights of Hanukkah. This is the same question Gauss answered when he was seven. Given the question in a context for creativity and with group collaboration, several of the second-graders came up with similar closed-form solutions.

Fibs for Small Fries

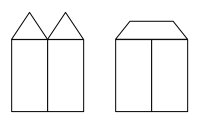

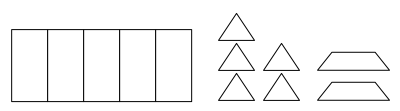

Another question was how many ways there are to roof a row of houses. The houses are connected, like brownstones in the city. There’s two styles of roof: a narrow roof covers one house; a wide roof covers two. There’s two ways to roof a row of houses.

How many ways are there to roof a row of five houses?

I believe this question was for fifth graders.

Getting Over Mr. Right

Sarah Allen writes about a story from John Holt’s book How Children Fail. The story itself is fascinating. (Read Sarah’s blog entry for more.) The larger context is the point that children are taught to play the “right answer game” instead of to learn how to learn.

Although I’m sure this is true in many classrooms, it’s no longer the state of the art in teaching methodologies. (It was never the state of the art among individual excellent teachers.) I think many parents, like myself five years ago, are limited to what they know from decades-old books and experiences or exposure to mediocre schools, and don’t have any idea of how far educational best practices have come.

Footnotes

-

“He” is a safe, although not universal, bet for a nineteenth century physician. ↩

-

Not to be confused with Marvin Minsky’s student Bob Lawler, who also studies the epistemology of math. ↩